What is Theory of Mind?

Theory of Mind (ToM) is our unique ability to reason about what is going on inside other people’s minds, including what they want (desires), what they know (knowledge), and what they think is true based on their prior experience (beliefs).

We use our “mind-reading” abilities every day, such as when we’re playing hide and seek, guessing our opponent’s next move in a game of chess, or figuring out why a friend is sad. Importantly, “mind-reading” does not mean that we can always read their minds accurately; rather, we use our intuitive understanding of how people think and feel in order to reason about what’s in their minds. In particular, our lab is interested in how ToM helps us teach and learn from others.

The “false-belief task” is often used to probe children’s developing Theory of Mind. After the first test of this ability in young children by Wimmer and Perner (1983), numerous versions of the false-belief task have been used with preschool-aged children (now there are non-verbal versions of these tasks that are used with infants!). Here’s an example of the false-belief task:

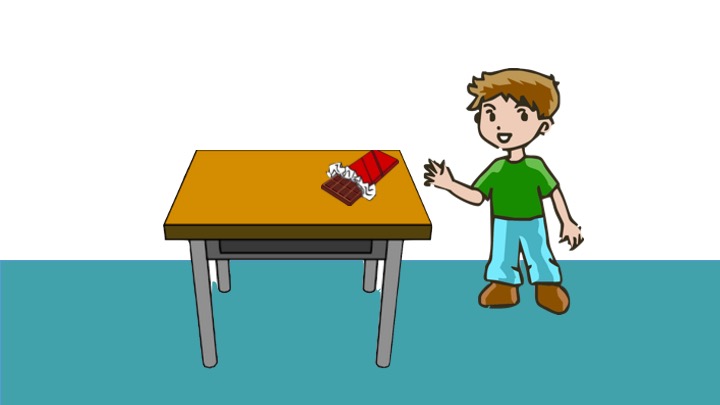

John is about to eat a piece of candy, but he has to leave for a moment. He puts it on a table.

Anna comes into the room while Tom is gone, and she puts the candy inside the table drawer.

Now, when John comes back, where will he think the candy is located?

That’s right ‒ on the table. In fact, he’ll probably be surprised when he doesn’t see his candy and won’t know where to look!

As adults, we know that John has a false belief about where the chocolate bar is located ‒ he thinks it is on the table, even though it isn’t anymore. However, if you show a 3-year-old this same situation, he or she will probably tell you that John will think that the chocolate is in the drawer.

This is because young children often have trouble holding two distinct perspectives ‒ i.e., “I think that the chocolate is in the drawer because I just saw Anna put it there” and “John thinks that the chocolate is on the table because he put it there and doesn’t know about Anna” ‒ in their heads at the same time, especially when they know the true state of the world.*

If you are interested in learning more about ToM, we recommend checking out these publications:

Gopnik, A., & Wellman, H. M. (1992). Why the child's theory of mind really is a theory. Mind & Language, 7(1-2), 145-171. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0017.1992.tb00202.x

Wellman, H. M., & Liu, D. (2004). Scaling of theory‐of‐mind tasks. Child Development, 75(2), 523-541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00691.x

Gweon, H. & Saxe, R. (2013). Developmental cognitive neuroscience of Theory of Mind. In J. Rubenstein & P. Rakic (Eds.), Neural Circuit Development and Function in the Brain: Comprehensive Developmental Neuroscience. Elsevier.

*Some research suggests that children under 3 can do this but can’t explicitly tell us about it. See this paper for more information!